“I like to think of the magazine as an archeological practice”

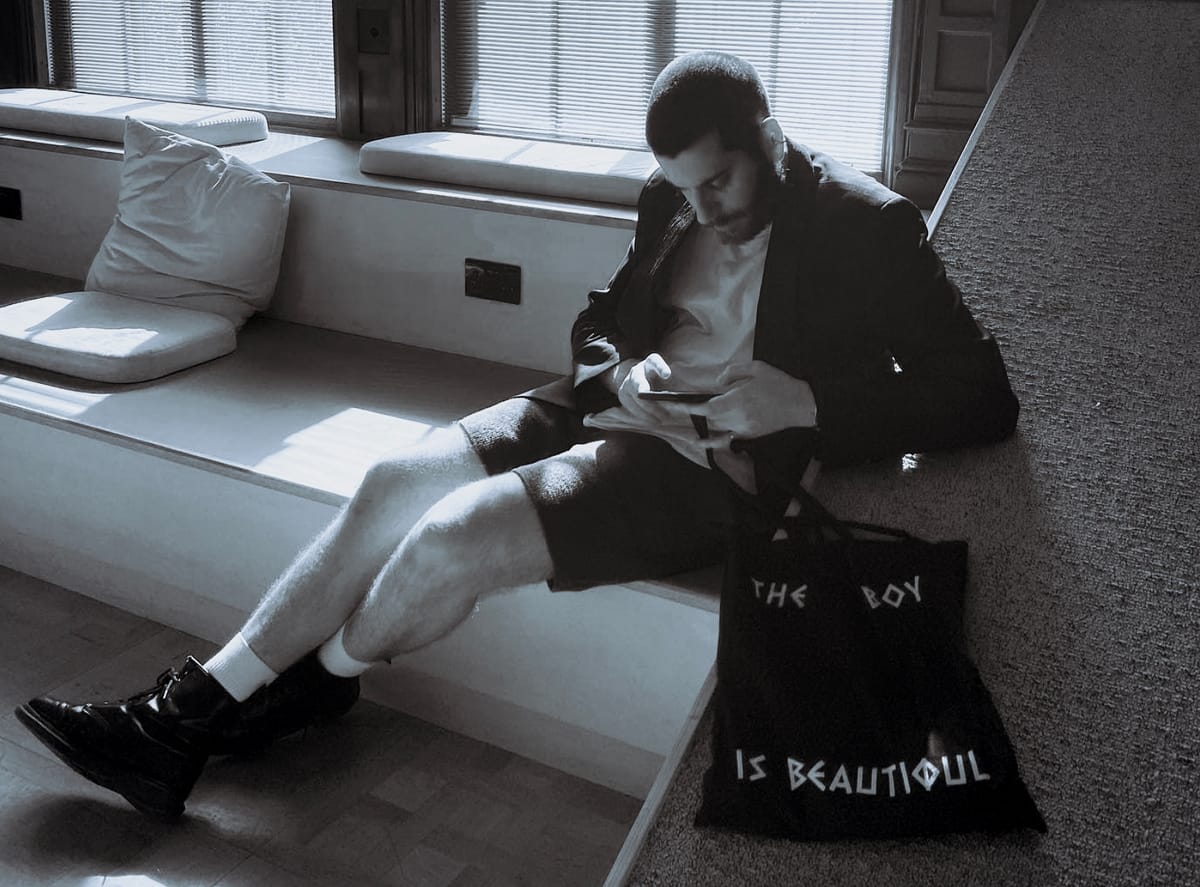

An interview with Leonidas Liolios, publisher and editor of "The Boy is Beautiful", a striking print celebration of queer Greek history and culture.

In one of my favourite bookshops in London recently, I recently came across a very Greek and very gay (i.e. right up my alley) magazine, The Boy is Beautiful.

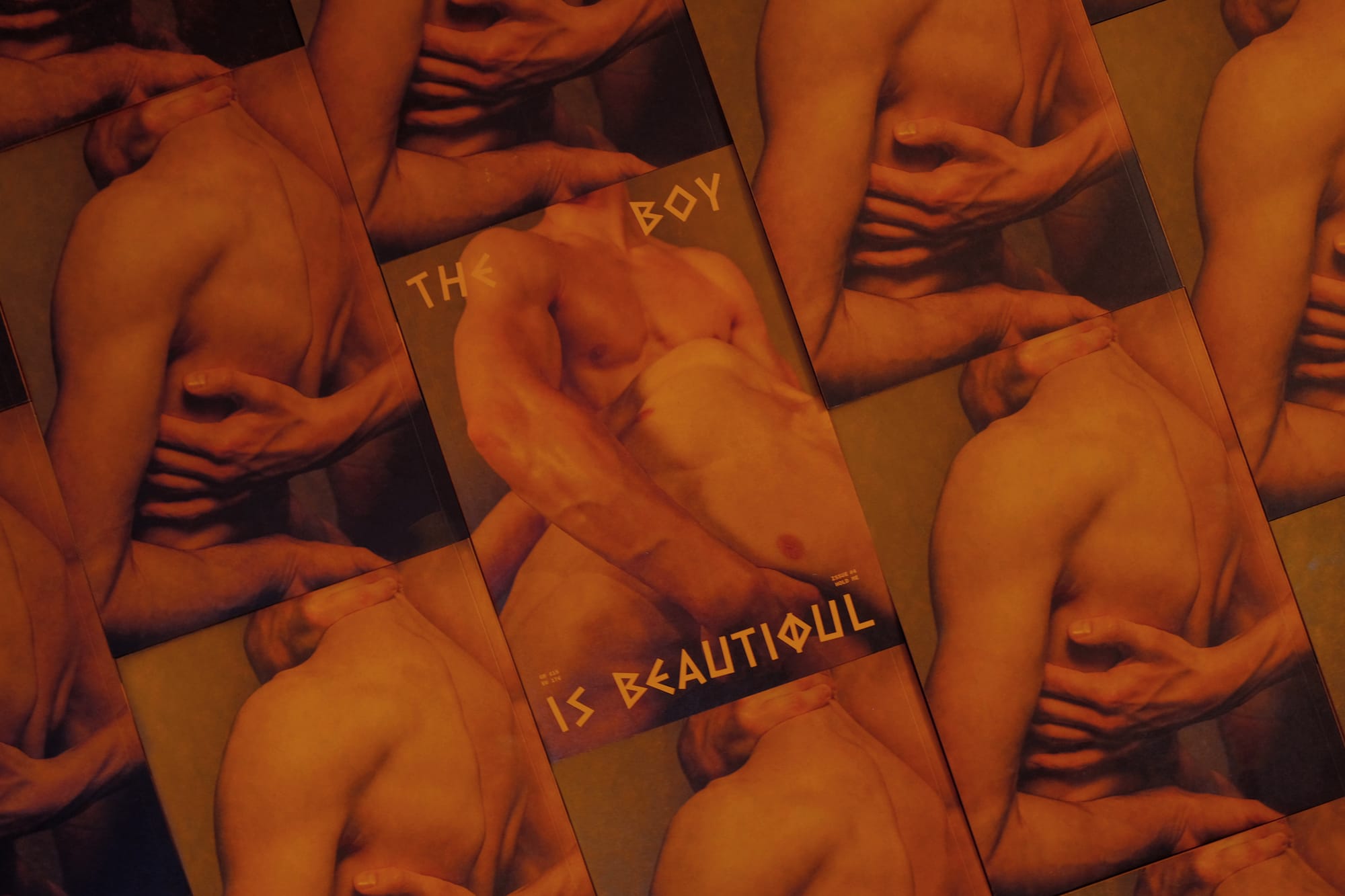

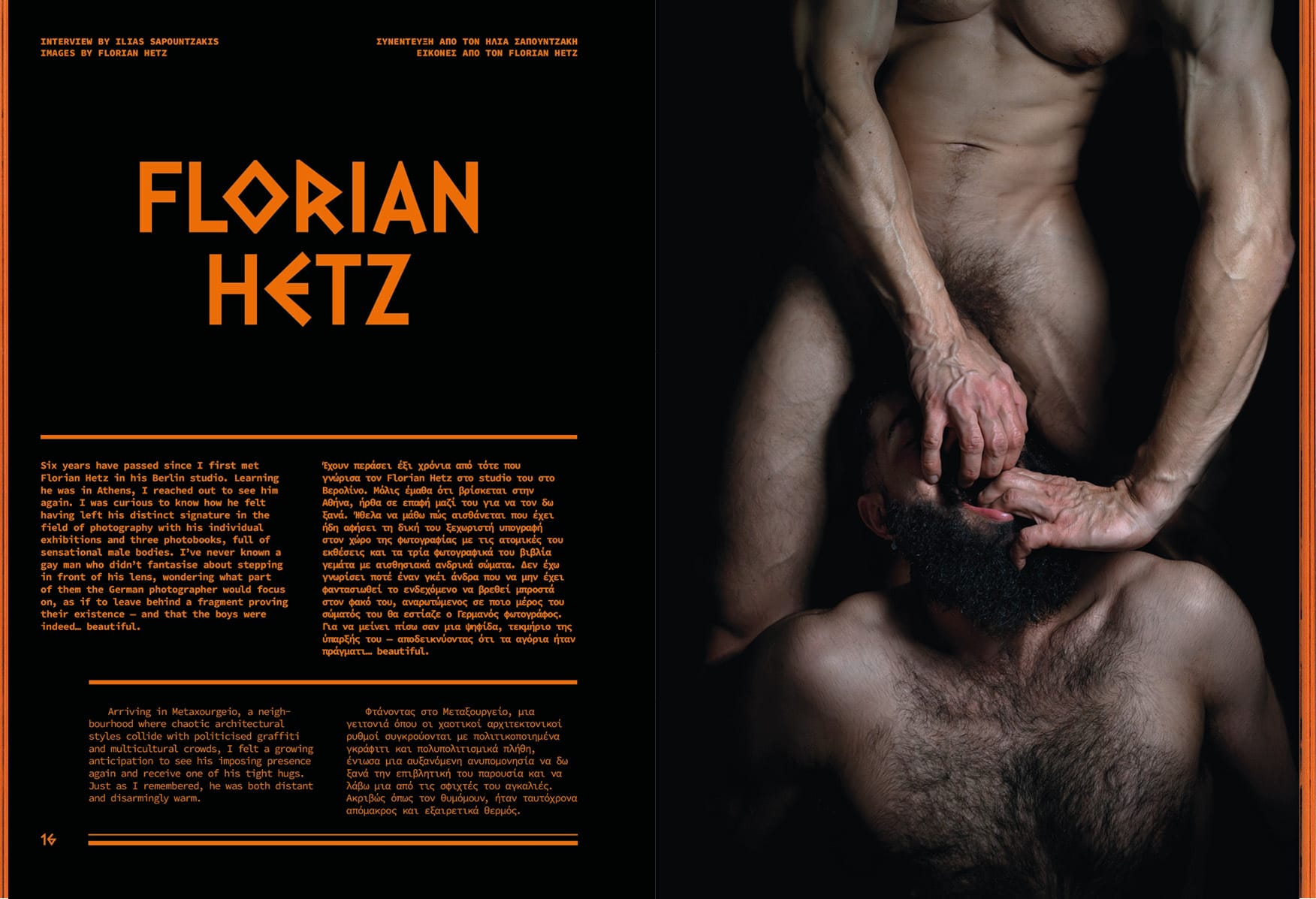

The Boy is a rare beast indeed – sexy, smutty and smart; an enticing, terracotta-hued blend of the erotic, the cultural and the political. I was keen to learn more, so I reached out to its founder, Leonidas Liolios, who answered the questions I threw his way with generosity and candour. Read on to discover how this beautiful bilingual print project embodies the excavation, celebration and reclamation of queer Greek history and culture.

Xander Beattie: It’s incredibly impressive to already have four beautiful issues of The Boy Is Beautiful (TBIB) under your belt. Tell me about the challenges, obstacles and joys you’ve faced as an editor and publisher along the way.

Leonidas Liolios: That’s very kind of you to say. You may know this already but Issue #1 of The Boy was my thesis project when studying at Central Saint Martins and so it presented itself as a real opportunity to deep dive into my culture as a queer Greek immigrant and flesh out an edition that was in a way a mission statement, not only for the title but also for my own practice. At first, I would print each copy by hand at the London Centre for Book Arts and later at Saint Martins, and so wrapping my head around the technicalities of that, making sure that each copy was perfect, that paper was delivered on time, that I cut it in the right grain direction and another million intricacies associated with print production were making up 90% of the challenges and obstacles I was facing at the time. Quickly the readership of the magazine grew from a few hundred to a few thousand and of course I was no longer printing it myself, but the joy I am feeling when I receive a proof from the printers is very similar to that of flicking through the first issue as it was pumped out of the press. And then there’s the joy of meeting so many incredibly talented people along the way, readers, contributors… with every fair, launch party, email or any sort of encounter prompted by The Boy Is Beautiful, I am reminded of why it all started and why it needs to keep going.

XB: While originally from Greece, you studied in London and you’re based there; the magazine is “designed, printed and published” in London while being undoubtedly a queer Greek journal. Tell me about what it’s like editing TBIB at a slight remove from its subject and inspirations. Does that distance help or hinder (or both?). What perspectives, opportunities (and even, potentially, drawbacks or disadvantages) does stewarding this project from London offer that you might not have if you were doing it from Greece itself?

LL: Had I not moved to London, The Boy Is Beautiful would not be a thing. I was desperate to leave Athens at the time as I could no longer see myself there. Through London and Londoners, I saw another side of the world and myself. I got to unpack my heritage and all the traumas that resulted from it. And with enough distance from Greece, I forgot the things that hurt me about it and focused on those that lure me back. When I was visiting Athens during the first years of living abroad, I was totally experiencing the city as a tourist. I developed a newfound interest in things I would walk past every single day when I used to live there. Through literature and books on mythology, walking about and looking at traces of classical architecture or even visiting the stolen marbles at the British Museum, I was rekindling my relationship with Greece on the daily, until I decided to tell my own version of it. It might also be relevant to mention here that even though The Boy explores facets of Greek queer culture, its community is international and not defined by borders or nationalities. We are all coming together cause at some point we bumped into a butt-naked Greek sculpture and clocked that it’s hot, and that we are not – and never were – alone in thinking that.

XB: On TBIB’s site, you describe the magazine as “a quest to figure out what happened between the time of Zeus and Ganymede, Apollo and Hyacinth, Achilles and Patroclus, the Band of Thebes and the Lesbian Sappho, Harmodius and Aristogeiton and my fascist, sexist, homophobic school mates, Thursdays’ straightwashed history lessons and Symposium-less Plato”. I’m curious to know over the course of the past four issues what has emerged during that quest… what insights or reflections or conclusions have you reached about the pendulum swing from the ancient tolerance of homosexuality in Greece to the bigotry you experienced at school?

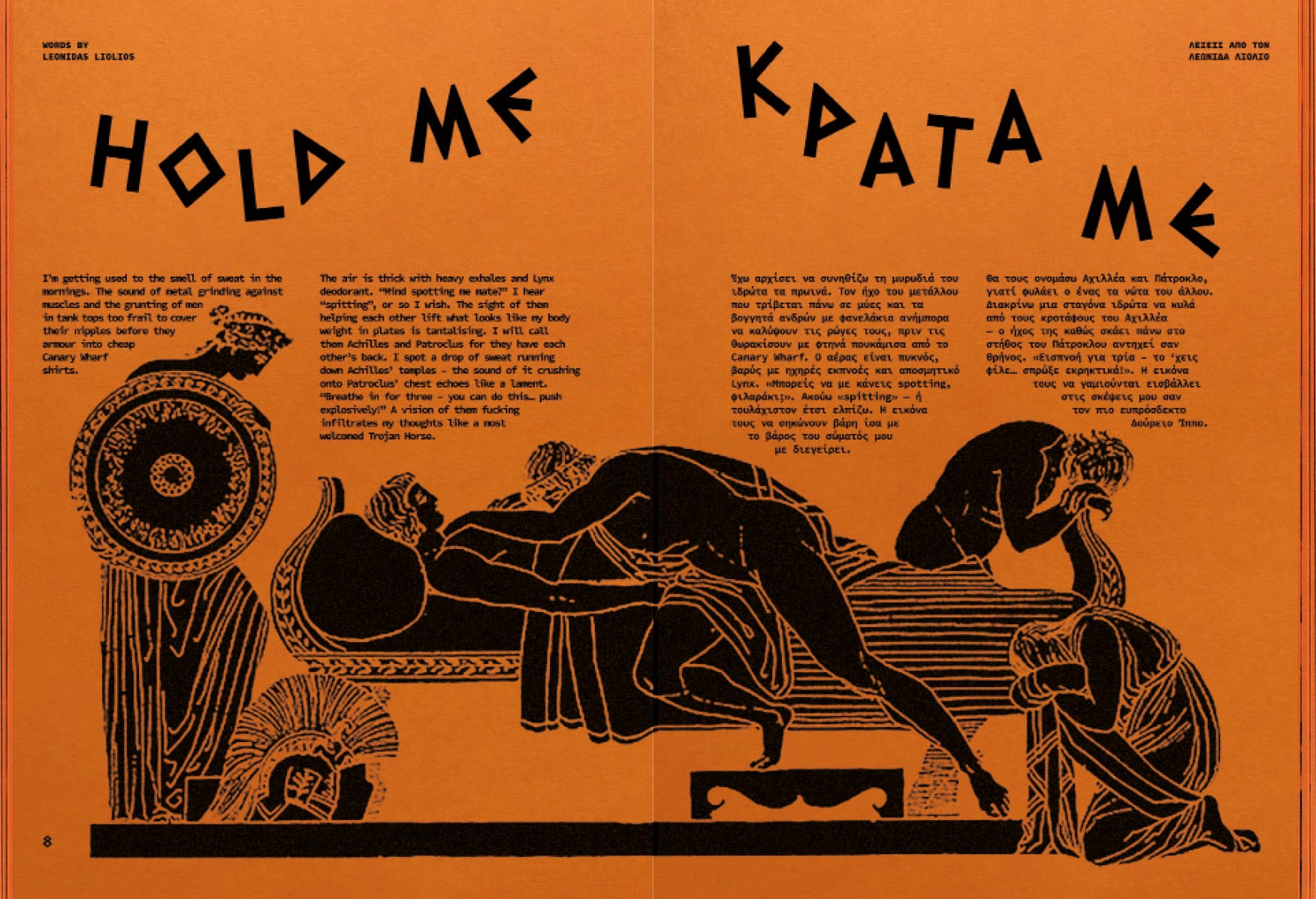

LL: I love this question and I could take forever responding to it but instead I think I am going to answer with an excerpt from one of my texts from Issue #4 that maybe does a better job at touching on what I’d define as the two pillars of oppression: religion and the patriarchy…

In torturous classrooms full of bullies with an “Agamemnonian” demeanour (loud, entitled and quick to make really bad decisions that will forever impact the lives of others), you won’t hear anything about Aeschylus’ scripts. Banter is reserved for Achilles’ lover, Briseis, the Stockholm syndromed Trojan priestess of Apollo, who kept Brad Pitt busy on the sandy dunes of Troy. In being a boy, and too close to the Iliad’s alpha-male, Patroclus was rendered minute, presented by heteronormative writers as a mere sidekick – his death reduced to collateral damage in a story fixated on the catastrophic consequences of a beautiful woman’s infidelity and that of petty jealousy amongst goddesses (think Apple of Discord).

And in the case of the Pasquino Group decorating the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence, little does it matter who the academics think the sculptures portray. Regardless if it’s Achilles or Menelaos holding the body of Patroclus, or even Ajax that of Achilles, homoeroticism is evident in the way they have been sculpted, fingers carving into flesh and veins pumped with erotic despair.

And yet, we’re still asked to look away. To unsee the tenderness in the grasp, the curve of care in those marble arms, the grief too intimate to be anything but love. We’re told it’s brotherhood, camaraderie, war-born loyalty. Anything but queerness. Anything but desire. History is bent into palatable shapes to ease the discomfort of those who’d rather see naked bodies than naked truths.

XB: What has the reaction been like to the magazine in Greece? And, in 2025, do you think contemporary Greece is becoming more accepting of queer sexualities or less?

LL: We just did a launch party at Hyper Hypo in Athens a few weeks ago and the vibe was incredible. It felt so emotional to be back home, speaking about The Boy Is Beautiful in Greek and listening to some of the texts being read in the context they were written… I love it when we receive messages on social media from people who have visited Hyper Hypo to get the latest issue of The Boy as if it’s part of their ritual of visiting Greece every summer. I was also thrilled that so many international people attended the event – I felt that part of the goal has already been achieved and we were all there to celebrate our shared ancient queer cultural heritage. Leaving the event space to get to our car, a guy on a bike shouted ‘faggot’ and rushed off. I thought there couldn’t have been a better ending to the night and I’m hoping this hints to my answer to your second question. With a government that’s openly hostile towards trans and non-binary individuals, and hostilities taking places against our trans and queer siblings on the daily, I can’t say it’s looking good. Sure, there’s progress on some regards, but look at the state of the world… America, the UK… our right to love and live are subject to crazy white dudes and deranged retired writers swimming in riches. I pity them for being silly enough to think they can get rid of us — they literally had about two thousand years to know better.

XB: How do you go about finding contributors, interviewees and material?

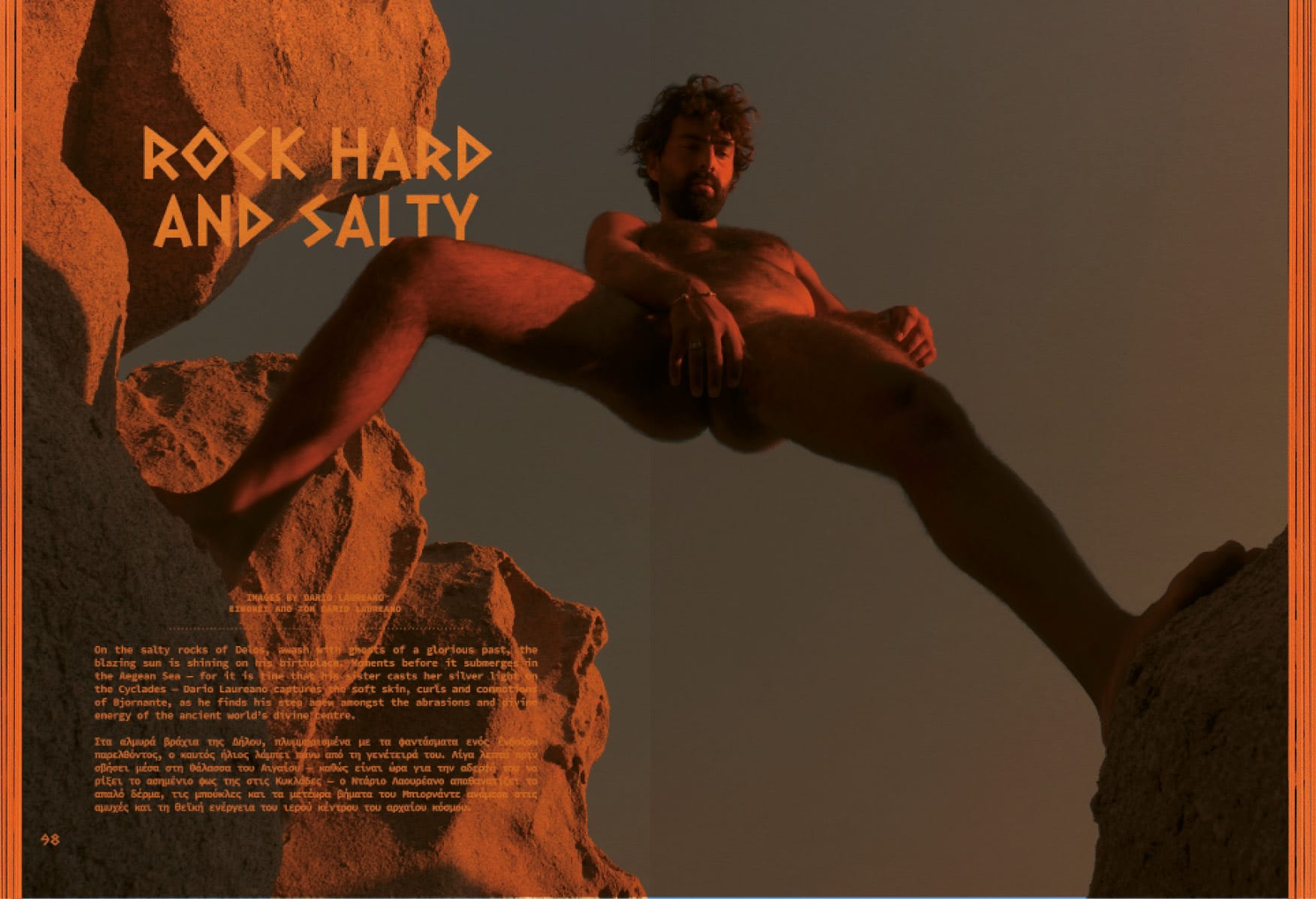

LL: It’s all an ongoing conversation. It happens really organically, and then things fall into place and a theme emerges. I will read a book or see a rendition of an ancient Greek tragedy, then meet an architect whose work will somehow relate to it and then see an image by a photographer who captures exactly that energy, and the theme would have suddenly emerged. I will then surrender to that idea and let it consume me, briefing the rest of the team on what we are looking for. Publishing one issue a year means that we really get a chance to dig deep, travel far and meet people in person so that interviews feel as intimate as the topics our discussions are touching on. I also like to think of the magazine as an archeological practice, unearthing and curating existing bodies of work together in ways that make new meaning.

XB: I love that TBIB is bilingual. While I have my own hunches as to why you may have chosen it to be both in Greek and English, I’d love to hear from you about your decision to offering the reader both languages — and what challenges (if any) this may have posed?

LL: Growing up, I didn’t know what queer love sounds like in my own language. It’s a strange concept to perceive, but imagine not knowing how two men would speak to each other in an intimate setting. The only Greek words that I knew that would relate to what I was figuring out to be my identity were either hurtful slurs or sexist and derogatory phrases. The one time there was a kiss between two men on television in Greece, the channel that aired it was fined twenty thousand euros. I was too young to even remember this and so my initiation to queer culture was through foreign tv shows like Queer As Folk and soft porn or full on porn Tumblrs. Cut to the lockdown and the OnlyFans boom that saw lots of Greek queers seeking for alternative sources of income or just a space to have some fun, we get to listen in to queers having sex in their own language, or were they? In a conversation for Issue #1 with OnlyFans performer IacovosOnly, he stated how he caught himself saying that word “fuck” all the time, and how that’s probably because he was only ever able to consume English gay porn. So, Greek is the language of trauma and not the language of queer love for many of us, which is totally ironic given our history. Our mission and the reason why it is so important for the magazine to be bilingual, is that we get to claim back our ability to love in our own language.

XB: How do you balance your career as a graphic communication designer and educator with your role as magazine editor? For people considering launching print publishing projects of their own, do you have any advice on how to juggle both career and project without going crazy?

LL: I think going ‘crazy’ is absolutely part of it, but in all seriousness I believe I am someone who gets bored quickly and so being able to jump between projects, teams and ideas keeps me going. Between exhibition design, teaching and publishing there’s the shared novelty of storytelling and aspiring to inspire and empower people and communities. I love both teaching and designing for galleries and museums, but I find that my publishing practice is where all of my learning and interests come together in perfect harmony, allowing me to fluidly move between the role of a designer, researcher, writer, editor, event producer, public speaker and so on. For now, I need all three to feel whole, and I think being in touch with what you want is the only piece of advice worth sharing.

XB: Who are your role models? When it comes to design and publishing, who are people and movements who inspire you?

I am forever moved by the poetry of Cavafy, Oscar Wilde’s obsession with Greece which had an impact on his work, urgent queer publishing movements of the 19th Century across the US, UK and Greece, Greek periodicals like Amphi and Lavris, with the former published by trans activist and icon Paola Revenioti. The brilliance of projects like S.I.R. Pocket Lawyer and some of the beautiful ephemera collected by the Rukus! collective in the UK. And later on, as a design student, the texts and practice of Paul Soulellis, titles like Little Joe, Pink Mince and generally the work of Dan Rhatigan (Hot Type Club) as well as Gert Jonkers and Jop van Bennekom’s BUTT magazine.

Aside from TBIB (of course!), for people curious about Greece’s queer life, history and culture, what do you recommend they seek out?

Books and films I think are always the best portals to places and eras either geographically or chronologically out of reach. Books like The Greeks and Greek Love by James Davidson, Omonoia 1980 by Giorgos Ioannou, Amphi Kai Apeleutherosi by Lukas Theodorakopoulos, the poems of Cavafy, the movies like Angelos by Giorgos Katakouzinos and Strella by Panos Koutras, and the paintings of Yannis Tsarouchis, the latter’s house and atelier in Marousi, wandering about SMUT’s darkrooms and just being naked under the scorching sun in one of Greece’s queer utopias… Anafi, Hydra, Samothrace to name a few.

- Check out Leonidas's website or give him a follow on Instagram. Issue four of The Boy is Beautiful is out now, available online, and from dozens of stockists worldwide.